Brain Tumour Information

Brain Tumour Information

Introduction

Defining a Brain Tumour

A brain tumour is defined as the sporadic and uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in the brain. This website will only discuss primary brain tumours - those that begin or arise within the brain. There are other types that spread to the brain but begin in another part of your body. These are called metastatic brain tumours. For more information about metastatic brain tumours please refer to websites that discuss where the tumour first occurred ie breast, lung etc.

Primary Brain Tumours

Primary brain tumours often involve the supporting cells or glial cells of the brain and are often referred to as glioma. Tumours of the nerve cells of the brain are relatively uncommon. Typically, the higher the pathology grade of tumour, the faster the growth compared to other tumours of the same type. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises four grades of glioma (I to IV), with IV being the most aggressive. Other primary “non glioma” brain tumours might involve the coverings or meninges of the brain eg. Meningioma These are often benign or non malignant but can be problematic as they compress brain structures and ultimately affect brain function. Again the WHO has a 1-3 classification system for these tumours depending on how active or aggressive they are. They are a multitude of other tumours that primarily affect the brain some with their activity best understood as as a spectrum from low grade /benign terminology to active tumours behaving in a malignant fashion. Some of these less common tumours are discussed below.

Recommendation

The location of a brain tumour determines how it will affect the function of your nervous system.

Some websites refer to glioma as brain cancers. We will refer to brain tumours however the terms tend to be interchangeable. As mentioned, even a lower grade tumour can be detrimental depending on its location in the brain.

This is a general summary of the different brain tumour types. However, we always recommend that you seek council from your treating doctors as a brain tumour diagnosis is highly individualised.

Brain Tumour Key Facts

General

- Brain tumours are defined as the collection or mass of abnormally growing cells inside the brain.

- Your skull is very rigid to protect the brain.

- The next layers within the skull are collectively known as the meninges. The first and toughest of these is called the dura mater – this is a thick layer of connective tissue that encases the brain, spinal cord and spinal nerves.

- The next layer is known as the arachnoid, a much more delicate layer that follows the creases of the brain and spinal nervous tissues.

- The cells of the brain are delicately encased in a blood brain barrier. This barrier is designed to keep things out such as microbes and toxins. The blood brain barrier is also very good at keeping out chemotherapies and other treatments. - Any growth within a restricted place can cause issues.

- Brain tumours may be referred to as cancerous (malignant) or non-cancerous (benign). This “black and white” so called fact is an oversimplification of a complex scenario where there are “shades of grey” between malignant and benign labels that are very important with respect to treatment and ultimately prognosis

- Both malignant and benign tumour growth can put pressure on the brain. This pressure can cause brain damage and be life threatening.

- The most common initial form of treatment for both malignant and benign tumours is surgery.

- The main aim of surgery is to biopsy the tumour, remove as much as possible without causing a permanent brain injury, then look at all options regarding all methods of controlling tumour growth such as radiotherapy/chemo/immune therapy.

What are Brain Tumours?

Primary brain tumours originate in your brain. They can develop from your:

- brain cells

- the membranes that surround your brain, the meninges

- nerve cells and the cells that surround them (known as glial cells)

- Pituitary gland

In adults, the most common types of brain tumours are gliomas and meningiomas.

What are the symptoms of a Brain Tumour?

The symptoms of a Brain Tumour widely vary from being very subtle (such as forgetfulness, change in moods, migraines) to very drastic (such as seizures).

This is not an exhaustive list of symptoms, however they are the most common:

- nausea

- headache

- vomiting

- seizure

- dizziness

- weakness of the arm, leg or both

- double vision

- speech problems

- behavioural changes

These symptoms can vary from person to person depending upon:

- location in the brain

- size of the tumour

- rate of tumour growth

What causes a Brain Tumour?

For the majority of brain tumours, the honest answer here is that we simply don’t know. There are numerous large population studies conducted world-wide (called epidemiology studies) to identify cause.

We do, however know that some brain tumours are caused by genetic and environmental reasons:

- Family History (although very rare in just 5-10% of cases)

- Age: Brain tumour incidence increases with older age

- Race: Brain tumours are more common in Caucasians

- Exposure to Radiation: People who have been exposed to ionizing radiation have an increased risk of brain tumours

- Exposure to Chemicals.

How are Brain Tumours Diagnosed?

Depending on the symptoms, people most commonly present to their General Practitioner (GP) or the Emergency Department (ED). The treating doctor will perform a comprehensive examination to work out exactly what is going on. They may assess:

- Vision

- Speech

- Reflexes

- Muscle strength

- Sensation

- Co-ordination

But the definitive test is to try and visualise what is happening in the brain.

- CT Scan

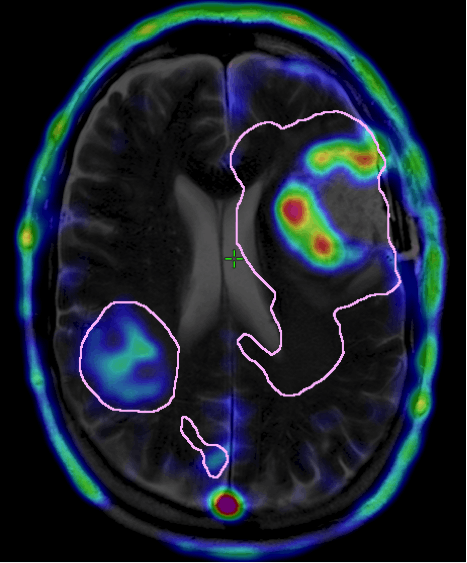

- MRI (higher resolution than CT)

A CT scan is often the first diagnostic test ordered if a brain problem is suspected as they are cheap and readily available. A dye (contrast) can be injected to better define what is happening in the brain (blood vessels).

An MRI is typically performed if the CT shows an abnormality. MRI scans generally provide a more detailed picture of the brain and its structures. Again, contrast can be added to a MRI scan to increase clarity.

How are Brain Tumours Treated?

As mentioned, abnormal growth in the brain puts immense pressure on the rest of the healthy brain. So most patients first undergo safe, maximal surgery. This may be a biopsy or resection/removal of the tumour depending on the risk /reward of operating in the part of the brain affected by the tumour.

Some brain tumours are best treated by other methods rather than surgery eg lymphoma/germinoma/certain glioma subtypes so the neurosurgeon has to weigh up the risk of surgery in regards to other methods that might be more optimal in the treatment of that particular tumour type.

There are several types of surgeries that will be recommended by your neurosurgeon based on the location of the tumour and the size of the tumour. Safety is paramount and the goal is to remove as much of the tumour as possible but to ensure the rest of the brain suffers no trauma.

Radiotherapy

Introduction

Radiotherapy has been the standard treatment for brain tumours for decades. New improvements in technology have enabled your radiotherapist to be more precise in their targeting of the tumour and minimising damage to the surrounding normal brain. Radiotherapy uses controlled doses of radiation to kill the tumour cells.

Radiotherapy occurs about 4-6 weeks after your surgery and can also be given with chemotherapy.

The exact nature of the radiation given is complex and depends on a number of factors. The treatment is often spread out over up to 6 weeks to minimise damage to tissues near to the tumour. The most important factor in deciding how radiation is given is tumour type, and also the tumour location.

Before you start radiation therapy, a radiation therapist will take measurements of your body and do a CT or MRI scan to work out the precise area to be treated.

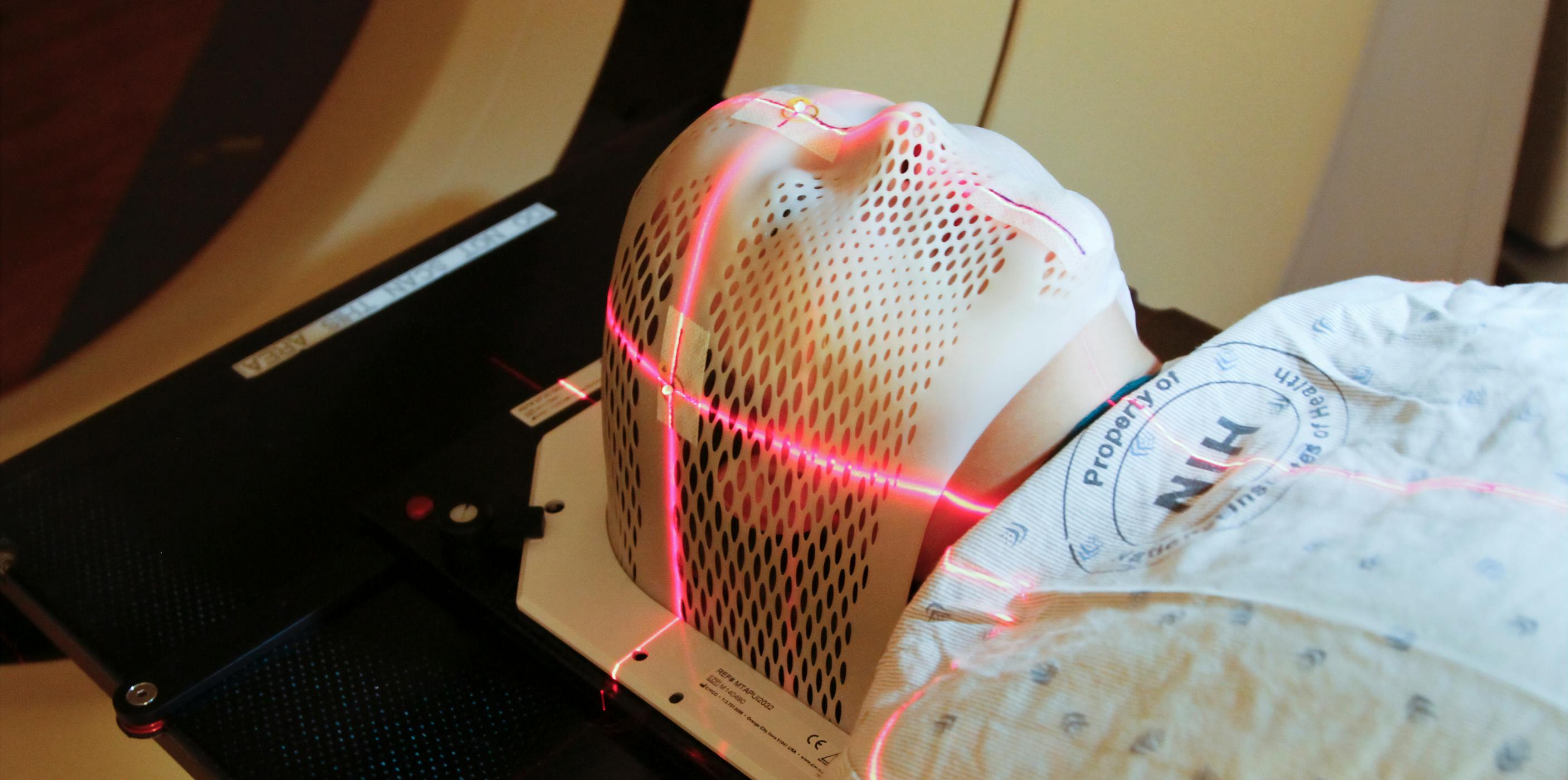

If you are having radiation therapy for a brain tumour, you will probably need to use a face mask. If you are having radiation therapy for a spinal cord tumour, some small marks may be tattooed on your skin to show the treatment area.

How often do you have to have radiotherapy?

Radiotherapy is usually given once a day, from Monday to Friday, for several weeks. During the treatment, you will lie on a table under a machine called a linear accelerator. Each daily treatment will last about 10-15 minutes. Radiotherapy is painless, however there are some possible side effects that will be discussed by your doctor with you.

Types of Radiotherapy

As technology advances, so too do the types of radiotherapy that you could receive. The most common type of radiotherapy is called stereotactic radiotherapy.

Stereotactic Radiotherapy (SRT)

A stereotactic radiosurgery machine is used to deliver a longer course of radiation, particularly for benign brain tumours. This is called stereotactic radiation therapy. The treatment is given as multiple small daily doses.

IMRT

IMRT is an advanced type of radiation therapy used to treat cancer and noncancerous tumours. Its highly technical but essentially uses advanced technology to manipulate photon and proton beams of radiation to conform to the shape of a tumour. IMRT uses multiple small photon or proton beams of varying intensities to precisely irradiate a tumour. The radiation intensity of each beam is controlled, and the beam shape changes throughout each treatment. The goal of IMRT is to conform the radiation dose to the target and to avoid or reduce exposure of healthy tissue to limit the side effects of treatment. Sterotactic radiosurgery is a technique where a specialized machine (gamma knife,x knife,novalis) is used to focus radiation on a defined tumour in order to kill the tumour cells. It is often given as a single treatment and is used to treat a wide variety of brain tumours. Because the majority of gliomas are not well defined it has a limited role in the treatment of many gliomas.

Radiotherapy FAQ's

Do I have to wear a face mask?

Yes, the plastic face mask, or immobilisation mask, is designed to keep your head still and to make certain that the radiation is directed to the same area during each session. Its made especially for you and fixed to the table.

The mask is made of a tight-fitting mesh, but you will wear it for only about 10 minutes at a time. You can see and breathe through the mask, but it may feel strange at first. Let the radiation therapist know if wearing the mask makes you feel anxious, as this can be managed with medicines.

What are the side effects?

Unfortunately there are side effects that generally occur in the treatment area. These side effects can be temporary, but some may last for a few months or years, or be permanent.

The main side effects experienced by patients include:

- nausea – often occurs several hours after treatment

- headaches – often occur during the course of treatment

- tiredness or fatigue – worse at the end of treatment; can continue to build after treatment, but usually improves over a month or so

- dry, itchy, red, sore or flaky skin – may occur in the treatment area, usually happens at the end of treatment and lasts one to two weeks before going away

- hair loss – may occur in the brain tumour treatment area and may be permanent

- dulled hearing – may occur if fluid builds up in the middle ear and may be permanent.

If you experience any of these side effects, talk to your radiation oncology team.

A small number of adults who have had radiation therapy to the brain have side effects that appear months or years after treatment. These are called late effects and can include symptoms such as poor memory, confusion and headaches. The problems that might develop depend on the part of the brain that was treated.

High-dose radiation to the pituitary gland can cause it to produce too much or too little of particular hormones. This can affect body temperature, growth, sleep, weight and appetite. The hormone levels in your pituitary gland will be monitored during treatment.

Chemotherapy

Introduction

Chemotherapy is designed to target the rapidly dividing and growing cancer cells. Most forms of chemotherapy work by “nicking” the DNA in the cancer cells and causing them to die.

You may have chemotherapy after surgery and/or at the same time as radiotherapy. This is called chemoradiation.

Types of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can now be given as a simple capsule (in the case of Temozolomide) that can be taken at home. Some chemotherapies can only be given through a drip (this is called intravenous chemotherapy). These treatments need to be administered in the out-patient clinic at the hospital. Your treatment with chemotherapy typically takes six months.

What are the common side effects from chemotherapy?

There are many possible side effects of chemotherapy, depending on the type of drugs you are given. Side effects may include:

- nausea or vomiting

- tiredness, fatigue and lack of energy

- increased risk of infection

- loss of appetite

- mouth sores and ulcers

- diarrhoea or constipation

- skin rash

- breathlessness due to low levels of red blood cells (anaemia)

- low levels of platelets (thrombocytopenia), increasing the risk of abnormal bleeding

- damage to ovaries or testicles, which can make you unable to have children naturally (infertile)

- reduction in the production of blood cells in the bone marrow; you may need to have their blood levels monitored regularly through regular blood tests.

It is rare to lose all your hair with the chemotherapy drugs used to treat brain and spinal cord tumours, although in some cases your hair may become thinner or patchy.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&rect=0%2C500%2C4000%2C2000&w=4000&h=2000)

Steroids

Introduction

Unfortunately, brain tumours as well as their treatments can cause swelling in the brain and leads to complications. Steroids, typically dexamethasone, is given to relieve and reduce this swelling, and can be given before, during and after surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. There are a number of side effects of steroids so your doctors will try and minimise the dose and time on these medications.

Can what I eat control my Brain Tumour?

There is no clinical evidence to support extreme diets and reducing brain tumour growth. A ketogenic diet is often mentioned in the press. Ketogenic diets are very low carbohydrate diets, usually with restricted protein, but with very high levels of fat. It‘s a very complicated diet to follow and can cause unpleasant side-effects, such as sickness, tiredness and constipation.

We suggest involving a dietician in your treatment team as a balanced diet and healthy eating is important. Some treatments may also turn you off certain food groups so its good to identify this.

Can exercise prolong my life?

There is no evidence that exercise can prolong survival, however mental wellbeing is critically important after the diagnosis of a brain tumour.

Exercise gets the endorphins in your body flowing and is well regarded by many clinicians. Endorphins are the “happy” hormones that can definitely help with mental illness and depression which are common in brain tumour patients. Make exercise fun!

Keeping generally fit and healthy will help your body in a number of ways not directly related to your brain tumour, so as always you should exercise as much as you can.

Types of Brain Tumours

Gliomas

Gliomas are the most common group of tumours in the brain and are thought to arise from the glial cells. The cells are supportive cells that surround the nerve cells to help them function properly. There are three main types of gliomas- astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas.

Gliomas Types

There are three major pathological grades of Astrocytoma:

- Diffuse Astrocytoma (Grade II)

- Anaplastic Astrocytoma (Grade III)

- Glioblastoma (GBM, Grade IV).

The aggressiveness (grade), location of your Astrocytoma in the brain and a molecular marker called IDH1 mutation determines your prognosis and treatment options.

An important concept to understand with astrocytomas, is that tumour cells almost always extend into brain that is functioning normally. This is true of tumours of all grades, but particularly the more high grade tumours.

This is typically an infiltrating tumour and does not have well defined margins (borders) which makes complete surgical removal difficult. Diffuse Astrocytomas are typically slow growing and occur in younger adults (20-40 years of age).

Depending on the size and location of the tumour, the first point of treatment is surgery with the primary objective to remove as much tumour as safely possible. Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy (RT) may also be suggested in addition to surgery depending upon its size, location and extent of surgical removal. Molecular features such as the presence of a mutation in the IDH1 genemay also help to define further treatments.

This is a more malignant tumour that can evolve from a prior Grade II Astrocytoma, but can also occur without any progression from a lower grade tumour. Anaplastic Astrocytomas (Grade III) have more aggressive features, including a higher pace of growth and more invasion in the brain.

As with Diffuse Astrocytoma, maximal safe surgery is offered to remove as much of the tumour as possible. Because Anaplastic Astrocytomas tend to be more invasive, it can be difficult to remove all tumour cells. Radiation Therapy will likely be suggested to treat the residual tumour cells. Chemotherapy may also be suggested to continue treatment after surgery. Molecular features such as the presence of a mutation in the IDH1 gene may also help to define further treatments.

In about 10% of people, GBM develops from a pre-existing Grade II or Grade III Astrocytoma. However the majority (90%) of GBM occur as the initial tumour. GBM is a highly aggressive tumour with pronounced brain invasion and very fast progression.

Patients with GBM are usually first treated with surgery but there are different reasons for surgery compared to its lower grade counterparts. Primarily surgery is used to: (1) collect a tissue sample for diagnosis; (2) to remove as much tumour as possible and (3) alleviate symptoms caused by tumour mass. Surgery is usually followed by Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy at the same time. This is referred to as concomitant treatment (or Stupp therapy, after the clinician who popularized the treatment). Another six cycles of chemotherapy are usually administered after the initial treatment period.

There are also some other types of astrocytoma that while they share the name “astrocytoma” they are very different tumours that behave completely differently to those listed above. Examples of these are pilocytic astrocytoma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma and ganglioglioma. These are all relatively rare tumours so consult your doctors about their specific treatment.

Oligodendrogliomas

These tumours arise from cells called oligodendrocytes (cells that wrap around and provide support to nerve fibres in the brain). Oligodendrogliomas can occur anywhere in the brain but are more commonly found in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Typical symptoms include headaches and seizures.

Oligodendroglioma Types

These tumours tend to grow slowly and appear slightly abnormal. Oligodendrogliomas tend to have a molecular aberration where two chromosomes lose their arms. This is called Loss of Heterozygosity of Chromosomes 1p and 19q (LOH 1p and 19q). Oligodendrogliomas usually harbour a mutation in the IDH1 gene.

Depending on the size and location of the tumour, patients are first treated with surgery to remove as much of the tumour as possible. If there is residual tumour cells, Radiation Therapy may be offered.

This is the highest grade of oligodendroglioma. In some cases, an anaplastic oligodendroglioma may develop as a result of progression from a Grade II oligodendroglioma. However, these tumours can present initially as an Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma. These tumours are more aggressive, grow more quickly and appears as abnormal cells. Loss of the chromosome arms 1p and 19q and IDH1 mutations define this tumour subtype.

Surgery is the first line of treatment offered for a person with an anaplastic oligodendroglioma with the intent of removing as much tumour as possible. Radiation Therapy followed by Chemotherapy is typically followed. These tumours tend to be highly sensitive to treatment.

Ependymomas

These can occur at any age but are more common to occur in young children. Ependymoma begins in the ependymal cells in the brain and spinal cord that line the passageways where the fluid (cerebrospinal fluid, CSF) that nourishes your brain flows. Typical symptoms include headaches, seizures and muscle weakness. Surgery is the primary treatment, but when the tumour can’t be fully removed or is aggressively growing, additional treatments such as Radiation Therapy or Chemotherapy may be recommended.

Ependymoma Classes

is slow growing and typically arises near a ventricle.

is slow growing and typically arises in the spinal cord. Ependymoma (Grade II) is the most common and typically arises within or near the ventricular system.

contain a specific fusion between the RELA and C11orf95 genes. These account for 70% of ependymomas that occur in the cerebellum.

is more rapidly growing and has a higher likelihood of recurring. These tumours typically occur in the cerebellum or brainstem.

Common Molecular Biomarkers

Introduction

Biomarkers are particular tests performed on tumours that help characterise them further. This will help your doctors guide their treatment, and to manage your expectations of what the tumour may mean for you.

Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1 and 2) mutations

IDH is a common gene involved in general respiration of your cells. The mutation results in a loss of normal enzymatic function and the abnormal production of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG). Prognostically, IDH mutations are one of the strongest prognostic markers in low-grade gliomas, but also high-grade gliomas. The majority of low-grade diffuse gliomas (astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas) are IDH-mutant. To test for IDH1 mutations, DNA from some of your tumour (stored in pathology at the time of your surgery) is extracted and sequenced. There is also a very simple immunohistochemistry (IHC) test that can detect IDH1 mutations in your tumour. The presence of an IDH1 mutation is a favourable prognostic marker, that is it means growth of the tumour is less aggressive. Importantly, treatments to directly target this molecular aberration are being developed and tested. IDH 2 mutations(another favourable marker) require DNA sequencing as there is no simple IHC test

LOH 1p 19q

Alterations in chromosomes within tumours are common. In particular, complete deletion of both the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p) and the long arm of chromosome 19 (19q) (1p/19q co-deletion) is the molecular genetic signature of oligodendrogliomas. This molecular event is thought to confer better response to chemotherapy.

MGMT

Another common change in tumours is called methylation. This is wear modification of part of the genetic material in the tumour cells results in the protein that gene codes for not being produced. This can be either good or bad depending on the exact gene involved.

Methylation of the methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) gene is suggested to confer better response for people diagnosed with GBM when treated with alkylating chemotherapies such as Temozolomide (TMZ). MGMT methylation is a specialised test that is often requested by your treating oncologist to guide their therapy decisions at the time of tumour recurrence.

Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG) (also called Diffuse Midline Glioma)

Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) or Diffuse Midline Gliomas are highly aggressive and difficult to treat brain tumours found at the base of the brain. They are glial tumours, meaning they arise from the brain's glial tissue — tissue made up of cells that help support and protect the brain's neurons. These tumours are found in an area of the brainstem (the lowest, stem-like part of the brain) called the pons, which controls many of the body’s most vital functions such as breathing, blood pressure, and heart rate.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas account for 10 percent of all childhood central nervous system tumours. DIPGs are usually diagnosed when children are between the ages of 5 and 9, they can occur at any age in childhood. These tumours occur in boys and girls equally and do not generally appear in adults.

Gliosarcoma

Gliosarcoma

Introduction

Gliosarcomas are very rare gliomas and can be defined as a glioblastoma consisting of gliomatous and sarcomatous components. Just 2.1% of GBM are gliosarcomas. They are most commonly present in the temporal lobe.

Treatment of Gliosarcoma

Surgery to biopsy then remove as much of the tumour as possible is the first line of treatment. Gliosarcomas are also treated with Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy.

Choroid Plexus Tumours

Introduction

Choroid plexus tumours arise from a structure in the brain called the choroid plexus. It lines the ventricles (fluid-filled cavities) of the brain and its primary function is to produce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Choroid plexus tumours almost always form within the ventricles. They can also form in other regions of the CNS. There are three Grades of Choroid Plexus tumours (Grade I-III). Grade I Choroid Plexus Papilloma are low grade and grow very slowly. Grade II atypical Choroid Plexus Papilloma tumours are of mid-grade and have a higher chance of growing back after being surgically removed. Grade III Choroid Plexus tumours are aggressive and invasive and are defined as malignant.

Treatment of Choroid Plexus Tumours

Surgery is the first line of treatment to safely remove as much tumour as possible. Depending on the Grade, Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy may be given.

Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumour (ATRT)

Introduction

Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumours (ATRTs) are high grade tumours of the central nervous system (CNS). Most ATRTs are caused by changes in a gene known as SMARCB1 (also called INI1). This gene normally signals proteins to stop tumour growth. But in ATRTs, SMARCB1 doesn’t function properly and tumour growth is uncontrolled. SMARCB1 can sometimes be found in a person’s DNA, which means they are born with it. ATRTs can form anywhere in the CNS. They often occur in the brain and often spread to the spinal cord. ATRTs occur in both children and adults and are very rare in both age groups. There have been only 50 reported cases in adults.

Treating ATRTs

The first treatment for an ATRT is surgery, if possible. The goal of surgery is to obtain tissue to determine the tumour type and to remove as much tumour as possible without causing more symptoms for the person. Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy may also be offered.

Medulloblastoma

Introduction

Medulloblastoma is the most common, high grade brain tumour in children. It is also called a Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumour (PNET). Medulloblastomas typically start in the back of the brain (cerebellum) which is involved in muscle co-ordination, balance and movement. Medulloblastoma tends to spread through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) — the fluid that surrounds and protects your brain and spinal cord — to other areas around the brain and spinal cord. Medulloblastoma is a type of embryonal tumour — a tumour that starts in the foetal (embryonic) cells in the brain.

Subtypes

Based on different types of gene mutations, there are at least four subtypes of medulloblastoma.

(1) WNT- activated

(2) SHH- activated

(3) Group 3 (non-WNT and non-SHH activated)

(4) Group 4 (non-WNT and non-SHH activated)

Treatment for Medulloblastomas

The goal of surgery is to take out as much tumour tissue as safely as possible. Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy usually follow surgery.

Meningiomas

Introduction

A meningioma is a tumour that arises from the meninges — the membranes that surround your brain and spinal cord. Although not technically a brain tumour, it is included in this category because it may compress or squeeze the adjacent brain, nerves and vessels. Meningioma is the most common type of tumour that forms in the head. Most meningiomas grow very slowly, often over many years without causing symptoms. But sometimes, their effects on nearby brain tissue, nerves or vessels may cause serious disability. Meningiomas occur more commonly in women and are often discovered at older ages, but may occur at any age. Because most meningiomas grow slowly, often without any significant signs and symptoms, they do not always require immediate treatment and may be monitored over time.

Grades of Meningioma

There are three grades of Meningioma (I-III):

- WHO Grade I meningiomas are low grade tumours and are the most common. This means the tumour cells grow slowly.

- WHO Grade II atypical meningiomas are mid-grade tumours. This means the tumours have a higher chance of coming back after being removed. The subtypes include choroid and clear cell meningioma.

WHO Grade III anaplastic meningiomas are malignant (cancerous). This means they are fast-growing tumours. The subtypes include papillary and rhabdoid meningioma.

Treatment of Meningiomas

Treatment of meningiomas depends predominantly on their location, size and their rate of growth.

Surgery is the commonest treatment for meningioma, as completely removing the tumour is often curative. Meningiomas range from being very safe to remove to very risky. Some meningiomas that are in risky locations may be treated initially with radiation therapy.

Radiation may be used in addition to surgery, particularly in many Grade II meningiomas and almost all Grade III meningiomas.

Schwannomas

Introduction

A schwannoma is a tumour that develops from the Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system or cranial nerves. Schwann cells assist conduction of nerve impulses. This type of tumour is usually benign. Schwannomas are sometimes called neurilemomas, neurolemomas, or neuromas.

Surgery is usually performed to remove schwannomas in the peripheral nervous system, although radiosurgery may by used for schwannomas in the head. Since they are found in the sheath surrounding the nerve, the procedure often can be completed without any damage to the nerve except for vestibular schwannomas where hearing is frequently lost after surgery. Smaller benign schwannomas may just be monitored. Other treatments, such as radiation, may be used in some cases.

Vestibular Schwannoma (formerly Acoustic Neuroma)

Vestibular Schwannoma, also known as acoustic neuroma, is a noncancerous and usually slow-growing tumour that develops on the one of the two nerves leading from your inner ear to your brain. Branches of this nerve directly influence your balance and hearing, and pressure from a vestibular schwannoma can cause hearing loss, ringing in your ear (tinnitus) and unsteadiness.

Vestibular schwannoma arises from the Schwann cells covering this nerve and grows slowly or not at all. Rarely, it may grow rapidly and become large enough to press against the brain and interfere with vital functions.

Schwannoma Treatments

Treatments for vestibular schwannoma include regular monitoring, radiation and surgical removal. The decision to treat, and which treatment is favourable depend on tumour size and precise location.

Craniopharyngioma

Introduction

Craniopharyngioma is a rare type of noncancerous (benign) brain tumour. Craniopharyngioma begins near the brain's pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control many body functions. As a craniopharyngioma slowly grows, it can affect the function of the pituitary gland and other nearby structures in the brain. Craniopharyngioma can occur at any age, but it occurs most often in children and older adults. Symptoms include gradual changes in vision, fatigue, excessive urination and headaches. Children with craniopharyngioma may grow slowly and may be smaller than expected.

Pituitary Tumours

Introduction

Pituitary tumours are abnormal growths that develop in your pituitary gland. Some pituitary tumours result in too much of the hormones that regulate important functions of your body. Some pituitary tumours can cause your pituitary gland to produce lower levels of hormones. These are termed, “Functioning” pituitary tumours.

Most pituitary tumours are noncancerous (benign) growths (adenomas). Adenomas remain in your pituitary gland or surrounding tissues and don't spread to other parts of your body.

Treatment

There are various options for treating pituitary tumours, including surgically removing/debulking the tumour, controlling its growth and managing your hormone levels with medications and radiotherapy techniques.